It has been a wonderful year at Marpa House

As the year draws to a close, we would like to send a huge thank you to all the helpers and staff who have kept Marpa House open and so busy this year.

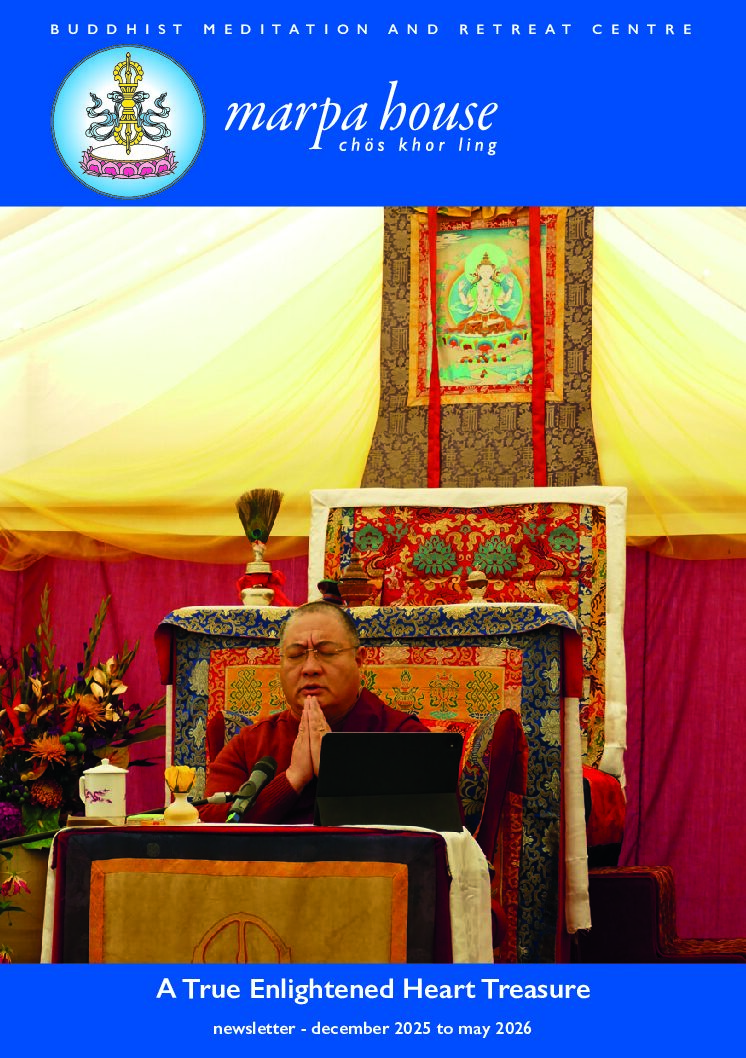

It has been a special year, and one with a significant landmark – the incredibly moving 50th anniversary celebrations. A weekend that deepened further our love and gratitude to Rinpoche for his inspiration and care, and for providing us with this very special and sacred place to practice and share meaningful moments.

We also had very special visits to the house by Shechen Rabjam Rinpoche, Tulku Pasang Rinpoche, Lama Kunga Dorje, Dorzin Lama Lungrik Nyima Rinpoche, Venerable Sean Price, Lama Alasdair, Lama Klaus, John Howard and David Crawford. Also, thanks to Sophie Muir, who started the year by leading us into 2025 with her New Year retreat. Our fantastic event team of volunteers has made these visits so blessed and beneficial for all who attended. You can see photos from some of these events here.

Our virtual shrine room continues to thrive, and we are deeply grateful to our dedicated Umzes, who lead our regular online pujas. This means we can all join in and practice together, regardless of our location or personal circumstances. If you would like to join us for Green Tara, Chenrezik or Calling the Lama from Afar, don’t hesitate to get in touch with us for more details.

We must also extend a huge thank you to everyone who has led a monthly Sunday meditation day, helped out on staff or covered at the house during 2025, for short periods or longer stints. These include (in no particular order, and with apologies for any omissions): Eva Ward, Janet Scott, Steffi Druege & Dieter Frank, Ruoyun Hui, Sue Sternberg, Payton Pitchford, Beth Laurels, Jaki Deere, Cherry Cooke, Dominique Simpson, Sarah Playden, Sarah Harrington, Pema Clark, Natasha Bolce, Mike Stone, Gudrun Schmidt & Brian Richardson, Iris Treibl, Maree Kearns, Loes Verbiesen & Jigme Radovic, Anne Westley, Imogen Hayman, Hartwin Busch, Iwona & Donald Reilly, Dan Bradley, Denby Birks, Horst Mueller, Udo Blumensaat, Joost Mooerbeck, Ulrike Heusne, Walter & Sascha, Emily Coates, Noriko Barter, Levi Reed, Keith Howell, Elizabeth Noakes, and, of course, Gabrielle McCarthy.

And finally, a big thank you to everyone who has visited, stayed at, or been on a retreat at the House, or attended a teaching this year, either in person or online.

We look forward to seeing you in 2026.