Before Marpa House…

The history of our building and grounds before it became Marpa House

Marpa House/Kham Tibetan House has a fascinating history, long before its current incarnation as the first Tibetan Buddhist Retreat centre in England.

Rinpoche was assisted in its initial founding and search for a suitable property by several kind students before what was then called ‘All Saints’ Home’ emerged as a potential location for Rinpoche’s centre.

The property was built in 1890 and has a very positive history, both in the building and the gardens, as ‘All Saints’ Home’ was a refuge for homeless children (mainly from London) for 83 years, from its inception by Dr Henry Swete. In fact, ‘Rectory Lane’ is still known by some locals as ‘Home Boys Lane’.

In the late nineteenth century, Dr Henry Swete, as the Lord of Ashdon Rectory Manor, was a very influential figure. He decided to provide a thatched cottage rent-free to the ‘Church of England Society for Providing Homes for Waifs and Strays’. At that time, many orphans were surviving on the streets in the big cities of England, notably in London.

Dr Swete paid half the cost of furnishing that cottage (now a private home). In 1885, the first group of boys arrived from London. At first, there were six children; then, three more followed quickly to fill the house. Each boy had a mall garden and attended the village school.

The original cottage, however, was in poor condition; so Dr Swete soon decided to build a new house for 12 children close to his Rectory and on land rented from Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. The new Home was opened on St Michael and All Angels’ Day in 1890 (29th September). After a service at the parish church, the clergy and congregation formed a procession led by a cross-bearer. They made their way to the Home, where Swete conducted a Benediction Service (a type of blessing).

The original cottage, however, was in poor condition; so Dr Swete soon decided to build a new house for 12 children close to his Rectory and on land rented from Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. The new Home was opened on St Michael and All Angels’ Day in 1890 (29th September). After a service at the parish church, the clergy and congregation formed a procession led by a cross-bearer. They made their way to the Home, where Swete conducted a Benediction Service (a type of blessing).

A local committee ran All Saints’ Home, and one of the most prominent early members of the committee was Mrs Brocklebank of Bartlow Hall. Bartlow is a village close by.

The first matron was Annie Wallis; her successor was Ellen Whitehead, who became matron in 1895 and remained in the position for 37 years, playing a significant part in the home’s history.

The first matron was Annie Wallis; her successor was Ellen Whitehead, who became matron in 1895 and remained in the position for 37 years, playing a significant part in the home’s history.

Problems with the water supply meant that the Home depended upon a nearby well. When this ran dry, water had to be carried up the steep hill from the village. This continued for 48 years, until a mains supply was eventually installed in 1938, the same year that the house was extended to accommodate more boys. The Home closed in 1961 for renovations and didn’t reopen until 1964. It finally closed in 1972.

From its dedication in 1890 until 1972, the house served as a refuge for boys aged 8 to 13. They came from diverse cultural backgrounds, and a few of the former residents have returned to revisit the house and grounds.

Further visits by original residents are welcome by appointment. Please get in touch with the Secretary at mail@marpahouse.org.uk

Paintings on the wall

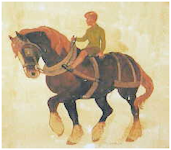

Around the walls of the original playroom in All Saints’ Home were hand-painted murals of local animals and people. Having been decorated over, they were lost for years. However, they were uncovered during renovations and redecoration of the shrine room at Marpa House, and some of the beautiful and unique paintings are shown here.

There is a small boy riding on a very large and striking horse called ‘Punch’, a man walking a harnessed working horse, and two pictures of dogs – one a domestic dog, and the other a hound.

All photographs are by courtesy of the late Mr. John Double, resident of Ashdon, and a former member of the All Saints’ Home committee.